- Home

- Cathy Guisewite

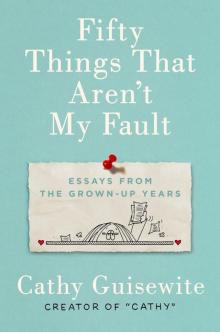

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault Page 13

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault Read online

Page 13

I remember carrying magazine articles about how to have more enlightened relationships in my purse and restudying them in the ladies’ room in the middle of dinner dates. I remember feeling filled with support and knowing exactly what to say until I sat back down at the table. I remember that not that many boys wanted a second date with a feminist.

It’s a little bit painful for my friend and me to see our daughters and remember who we were when we were their age. The very best years of our lives—when we were young and pretty and bursting with hope, innocence, and optimism. When love should have been welcomed, not feared. When we had so much to give and so often gave it to the wrong people. It helps to play it back with someone who was there. It’s a tribute to the power of female friendship that my friend and I are still speaking to each other. We look at each other now and shake our heads—for all the bad choices we helped each other make, for all those dreams and delusions we supported.

“I hate you,” I say, laughing warmly, toasting my friend with what’s left of my latte.

“I hate you more.” She laughs just as warmly, toasting me back.

“At least we’re done now, aren’t we?” I ask. “We’re safely on the other side.”

“Oh, yes!” she answers. “Thank heavens those years are behind us. We survived. It’s a whole different world for our girls. Things are complicated for them, but they won’t have an entire society to transform while they try to date. They’ll be fine. I’m so happy and relieved I can be done with love.”

“Me too,” I say. “I’ve had a wonderful life, but I feel as if I’m finally back to who I am. My own home, my dog, my daughter. I’m grateful I had love in my life, but I’m thrilled to be done with it now.”

“One hundred percent done!” she echoes.

“So done!” I echo her echo.

We hug, promise to not let so much time pass before we see each other next, and pay the check.

We’re just about to reach the door of the restaurant to leave when a man steps in front of us. Handsome. Sky-blue eyes. He smiles and opens the door with a Prince Charming sweep of his arm. My friend thanks him with an involuntary middle school giggle. I’m mortified to feel myself blush.

We are so done with love. Love, on the other hand, will apparently never quite be finished with us.

22.

THE DAY I WASHED MY FACE WITH BATH SOAP

Tell me about your skin care regimen!” the department store cosmetician cooed, admiring my young, innocent skin and welcoming me into the Club. This was decades ago, back when I had young, innocent skin and, as salespeople quickly gleaned, a young, innocent charge card in my purse to match.

“What do you use to wash your face?” she asked eagerly, inviting confidence and sisterhood.

“Soap!” I answered proudly, encouraged by her warm reception.

“Soap??” She leaned in, seeming riveted.

“Yes!” I replied, thrilled that I knew the answer to the first question on the very first day I was brave enough to approach the department store cosmetics counter. “Yes! I always wash my face with soap!”

“Bath soap??” She gasped.

I didn’t know what I’d done wrong, only that I was apparently no longer in the Club. I remember being hit with an overpowering blast of perfume as all the other cosmeticians in the department whipped their heads around to stare, sending all their over-the-top scents in my direction. I suddenly reeked of Wrong Answer. I turned all the colors of blush in my cosmetician’s display. I felt very unproud.

We don’t wash our faces with soap, I learned. We cleanse with a gentle, non-detergent facial cleanser. The cleanser is to be preceded by a hypoallergenic makeup and environmental toxin remover . . . then a mild exfoliating scrub . . . then the cleanser . . . then toner, serum, targeted fillers, and plumpers . . . and then we can start the complex moisturizing system, a different product for each dry or oily zone.

It took $235 to buy my way back into the cosmetician’s favor. Just to get to a clean face. Just to achieve the blank facade upon which I could, if I ever got a raise or was willing to skip a rent payment or two, begin to build my look.

It took two showers to lose the aroma of failure when I got home.

It took decades to lose the mental residue of being scolded for not knowing how to be a girl.

Who knows why we finally snap, but it finally happened. Today. 6:30 a.m. Cup of coffee number two. I rise up from the newspaper at the kitchen table. Stomp down the hall in my pajamas. Fling open the bathroom door. Power-glare at my morning face in the mirror. I grab a bar of soap from the plastic dish on the edge of the tub. Lean over the sink and for the first time in many years . . .

Wash my face with bath soap!

HAH.

I step back from the sink. No beauty alarms are blaring. I peek out the bathroom door. No police standing in the hall. I look in the mirror. No flaking, cracking, blotching, or any of the other signs of skin damage I was warned would occur if soap ever touched my face. I can’t believe it. My mind reels with rebellion.

What other naughty things can I do?

I reach under the sink, pull out an economy-size container of cheap discount store body lotion, squirt out a big blob, and use it to moisturize my face. I peek out the bathroom door again. Still no police. Hah.

The next hour is a beautiful blur of defiance.

I pull my hair into a ponytail without worrying that there are no cute casual wisps framing my face! . . . I pour cereal in a bowl without measuring three fourths of a cup! . . . Add berries without counting them! . . . Make new coffee with whole milk and real sugar!

I’m giddy with anarchy. What’s next? Lashes without mascara? Lips without gloss? Thighs without Spanx? Chocolate without guilt? Thank-you notes without apologies? White bread? Without fake butter? Outdoors without shoes? HAH!

I run out of my house in my pajamas and stand barefoot right in the middle of the yard. I lift my unsunscreened face to the early morning sun for a full two seconds.

I like being a woman. I like rules, structure, and tips. I want to fit into the Club, or at least be somewhere on the edge of the Club. But the thousands of dollars I’ve spent on skin care trying to preserve a youthful look and my decades of obedience to the rules of womanhood were never quite as rejuvenating as this.

I wiggle my bare toes in the grass and make a pledge to myself, to the part of me that got lost at the cosmetics counter that first day years ago. From now on, I promise to take fewer steps trying to achieve a “dewy face” and to take a lot more steps that lead to the happiness I’m standing on right now: dewy feet.

23.

IT TOOK A VILLAGE

Stray socks on the kitchen counter . . . sweat shirts draped over the back of the couch . . . shoes, tights, and school papers dropped in a path down the hall . . .

I follow the trail of my daughter into her bedroom. I take a deep breath of the last nineteen years: Love Spell body mist mixed with the memory of dried finger paint. Saucy tank tops and SpongeBob SquarePants pj’s spilling out of open drawers. A jumble of little girl fantasies and big girl dreams: Magic wands and miniskirts. Strapless bra on a Tinker Bell blanket. Fishnet tights hanging from 101 Dalmatians hooks. Tangled necklaces. Mangled power cords. A desk covered with everything but a place to do schoolwork. A heap of T-shirts and tiny teen dresses on the floor of the open closet.

I allow myself a wistful moment to take it in, to imagine how I’ll miss it when my daughter packs it all up and moves back to college after her break. The emptiness. The unbelievable, unbearable emptiness of her being gone.

I only allow myself a moment because she left two days ago.

This isn’t everything she’s about to take. This is what’s still here after she already took everything. As though a whole civilization of teenage girls had to evacuate with no time to grab their belongings. That’s how it looks in this room. E

xcept she had lots of time to grab things. We had to buy an extra suitcase for all she grabbed. This is what’s left.

“You forgot this top!” I said, lifting a cute almost-new one from her laundry basket after she finished packing her last suitcase the night before she went back to school.

“I hate that top,” she scoffed.

“You loved it when you begged me to buy it for you! What about these leggings?” I asked, picking a pair out of the pile on the floor. “This cute jacket??”

“Mom, you told me to pack and I packed!!” she whined.

“But you’re leaving behind so many cute things!” I implored, gesturing to the room. “So many perfect school clothes!”

“No one wears school clothes to college!” she argued.

“Excuse me??” I asked, exhausted and spent—literally spent, after a week of Target, mall, and drugstore runs.

“NO ONE WEARS SCHOOL CLOTHES TO COLLEGE!!” she snapped.

Scoffed. Whined. Argued. Snapped. After everythi— But never mind . . .

I sit on my daughter’s bed and sigh. I take another deep breath of her room. I try to find my happy-mom place between how sad I am that she’s gone and how glad I am that she left.

I need my village. My support system. I need Bob, a dear friend who’s been part of our family forever and has helped me through so many transitions.

“Teenagers get obnoxious so we won’t miss them so much! It’s their gift to us,” I say to comfort myself, but also to comfort Bob, who surely felt as hurt as I did when he heard what my daughter said. Yes, Bob’s right here too and was also here that night. He witnessed the whole thing. He actually looks more wounded than I felt because our dog ate half of his rubber nose and one of his plastic eyes the day my daughter brought him home from the fair when she was three. I pick him up from the other side of the bed: Bob, the stuffed rabbit. Our dog never cared about ears, so Bob heard everything that ever went on in this room, even all kinds of things it’s probably best he never shared.

“Teenagers also get obnoxious so they won’t miss us so much,” I say to formerly identical twin polar bear cubs, Meg and Peg, from the Los Angeles Zoo gift shop, who also watched the mother-daughter packing drama. Peg was the victim of a grape Slurpee accident when my daughter was five. Sad for Peg, but we decided permanently purple fur was a good thing. It helped us talk about not feeling bad when you feel different. Also, we agreed it made Peg a more patient listener because we quit calling her by her sister’s name half the time.

I pick up Mary, the stuffed golden retriever puppy my daughter carried everywhere for years. A being so crucial to everyone’s sanity that when we realized Mary had been left at a hotel at Legoland AFTER we’d driven three hours home, I called an emergency babysitter to put my girl to bed, got back in the car, and drove three hours back to the hotel to rescue her—then three more hours back home. “She wanted you with her at college,” I say tenderly to Mary, holding her up, “but she needed room in her suitcase for two hundred dollars’ worth of hair products. None of us can take this personally.” I give her a kiss on what our real-life dog left of her nose.

When they say “It takes a village,” I’m pretty sure they mean a village of humans, but I’m also pretty sure people lean on whoever’s available. My family lived far away in different time zones . . . Friends were busy with their own lives . . . The Internet didn’t exist yet . . . I was single . . . and was too busy, proud, and clueless to ask for or even know I needed help when I did.

This was my village a lot of the time, especially in the beginning. I scan the mostly half-blind, de-nosed, partly hairless, matted menagerie piled on the bed, lining the bookshelves, and plopped in a corner of the room—stuffed dogs, bears, cats, birds, and one beloved tiger with a satin ribbon around her neck on which a faded Hayley is written in wobbly first-grade printing. Some members of the village are still half dressed in costumes, as if my daughter outgrew them right in the middle of a game. I know all their names and histories better than I know those of many of the people in my life. They know more about my daughter and me than anyone on earth. They saw it all, from the very beginning.

The elders of the village—the stuffed animals who were here when I brought my daughter home from the hospital—saw how my precious new baby snuggled so trustingly in my clueless new-mom arms that first night. They saw how completely overwhelmed I was by how instantly she accepted me as her mother. How surreal it was for me to sit with her in the rocking chair I never imagined would be in my single-person home . . . to feel her relax into sleep as I fed her. They saw me gaze at her tiny perfect face, gently rock her, and lovingly sing her very first lullaby.

They saw how she woke up screaming the second I started singing.

Every single time I started singing. They saw how, by the end of night two and forty-eight hours of no sleep, I admitted that my voice might be the problem, staggered to the other room, and brought back a tape player and a stack of professionally recorded lullabies I’d been given as baby gifts. They saw how I silently mouthed the words as my baby was lulled to sleep by the audiotapes, the satisfaction I got from pretending Dionne Warwick’s voice was coming out of my mouth.

My village is a nonjudgmental group. None of them ever felt the need to mention how some version of what happened that night, three days into motherhood, got repeated thousands of times throughout the nineteen years that followed: my learning to understand and appreciate who my daughter is, to respect her opinion, to give her what she needs, all the while trying to hang on to some little shred of how I planned for things to go . . .

All those beautiful stroller walks we started, with me joyfully pushing her as I introduced her to the trees, birds, and flowers . . . that ended with me carrying her home wailing because, I finally accepted, I had the one baby on earth who hated being in a stroller.

All the mingle ’n’ jingle groups, the tiny tots dance classes, the sing-along sessions, the junior gyms, the wee ones soccer leagues, the art for little people places we joined and abandoned because she refused to mingle, jingle, dance, sing, tumble, play soccer, do art . . . or, basically, leave my lap.

All the fantasies of meeting friends for leisurely Sunday brunches, my darling daughter in a booster seat by my side . . . that for reasons I don’t need to recount, turned into many, many carry-out containers of pancakes we ate at home in our own kitchen by ourselves.

Even all my dreams of teaching her to eat a proper breakfast at home at the table with nice manners . . . how they deteriorated into her on all fours on the kitchen floor lapping cereal and milk out of a bowl with her tongue during a long phase in which she had “turned into a cat” . . . And how, when visiting friends saw her and were horrified by how I’d caved in to my child’s whims, I put a bowl on the floor next to hers and ate my cereal there on all fours too, meowing like the mother cat I needed at that moment to be.

My daughter and I bonded deeply right from the start over all the things we discovered that we loved together—dogs, the park, playing dress-up, painting on the porch, baking, reading books, inventing stories, building castles out of blocks, sand, and cardboard boxes.

But we bonded just as deeply, or even more so, over things that seemed to come easily to others that were hard for her and then so hard for me. We were a team. Defiant survivors of her early childhood—playgroups she didn’t fit into, a school system not set up for how she could learn, activities where she felt lost or left out . . . testing, tutors . . . all those horrible looks from other mothers whose children didn’t melt down at the mall, bite the dentist, or have humiliating full-blown panic attacks every time they boarded an airplane. We got through all that . . . hauled her through the academics . . . then the nightmare of middle school girls, then the nightmare of high school boys . . .

I went into motherhood planning to be a serene, self-assured role model of accomplishment, sharing the strategies and tips that helped me b

e successful. A fount of wisdom. That’s what I planned.

My child wanted none of it.

Stories of my accomplishments only made my daughter, who struggled to do some of the most basic things, feel worse about herself. Tales of how good old-fashioned hard work easily led to me getting great grades and a wonderful career made her want to quit. She worked harder than lots of kids, and nothing came easily. My wisdom demoralized her. My perky tips made her angry.

My daughter wanted confessions. She wanted to hear about my failures, fears, embarrassments—the worse, the better. The more humiliating, the more reassuring.

Did you ever wear your shoes on the wrong foot?

Did you ever get called on in class and start crying in front of everyone?

Did you ever spell your own name wrong?

Did you ever sit down for lunch and have all the other girls get up and leave?

Did you ever spill a whole drink in your lap?

Things like that. Stories of how I froze with fear and couldn’t speak to the cute boy on the playground gave her hope. Stories of how I chatted with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show did not.

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault