- Home

- Cathy Guisewite

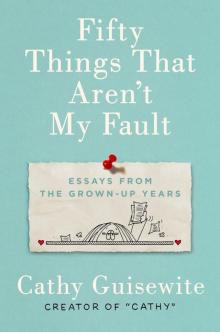

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault Page 5

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault Read online

Page 5

I stayed in bed alone the rest of that evening. I put The Sound of Music in the drawer. I ate the pint of ice cream by myself, one spoon in each hand. When I was done, I reread all the books.

In case she ever had another question, I would be ready.

Saturday, 9:33 a.m.

I turn back to my shoe wasteland, metaphor for this special time of life. A closet full of pointy stiletto thorns stabbing my delusion that nothing’s changed.

I pick up my open-toed, open-sided, open-backed, dainty ankle-strap-wrapped heels, which gave me shin splints and back pain and threw my whole body out of alignment, but which were going to make Rick Somebody or Other love me.

I pick up my first “career girl” pumps, which not only promised to give me the cool, professional authority of the big boys in the office, but which took three inches off my thighs.

I pick up my beloved royal blue satin sling-backs. I remember the night I committed completely enough to finally step off the carpet in them, the exact spot on the sidewalk where I felt the first scratch on their soles. It was the moment that made these shoes mine forever. Unreturnable. Like a first kiss. I remember how after that, I could walk into any room fearlessly if these sling-backs held my feet.

They aren’t just shoes, after all. They’re mini-marriages, performed in that most perfect wedding chapel, the shoe department. The only place on earth that has mirrors that only show the body from the knees down. Marriages cheered by shoe department strangers: “Cute!” “I LOVE those!” Blessed by friends and family, at least the female ones: “Where did you FIND those?!” “They’re PERFECT! PERFECT for you!” Over a lifetime, hundreds of sacred ceremonies for the feet. Vows of commitment. Rationalizations recited like wedding poems.

Nobody told me the bride would wake up one day with middle-aged bone spread and have to walk away from every pair in giant fickle naked feet.

I hold up my silver Cinderella wedding shoes. I glow inside, remembering the one-mother-two-sisters-five-girlfriends-three-month-fifty-seven-shoe-store search for them. I parted with the man I married—but I will never ever part with the shoes that walked me down the aisle. Is that so wrong?

Then again, when have I ever given shoes away? The really worn ones have been down way too many roads with me. The hardly worn ones are still waiting for their big chance. The piles of shoes in between have exactly fit who I was the day I fell in love with them, an irreplaceable diary of my heart written in saucy boots, no-nonsense pumps, shiny stilts, goofy wedges.

Whose feet could I ever trust to walk in all these memories and dreams?

Deep breath. It takes a while . . .

Maybe my beloved shoes have brought me exactly as far as they should.

Maybe, I think, they’ve walked me right to this new rite of passage.

Saturday, 9:45 a.m.

Finally I call my daughter in.

I silently lead her to my closet. I was wrong to lock her out before. This is exactly the time to share what’s ahead more fully than my mom was able to share it with me.

I look at my great big little girl and her innocent nineteen-year-old size 7 feet. I put my arm around her and gesture toward my closet. On this dark day when all my shoes are lost to me, I see the light in her. My legacy. With my love and guidance, she can literally walk in my shoes.

And so I offer it all to her. My soul. My soles.

“Honey . . .” I start. “I want to talk to you about some big and beautiful changes, let you know it’s not so scary, it’s just part of life. Someday . . .” I pause. I’m so overwhelmed, I can barely speak. “Someday you’ll stand at your closet just like this with a daughter of your own and you’ll remember this moment with me. I’m passing all I know on to you, honey, just like you will one day pass it on to your daughter. That is, if you’ll have them.” I gesture tearfully. “Would you . . . would you like my beautiful shoes?”

She squints into my closet.

“Those?”

“Yes,” I choke. “Remember when you were little, how your tiny three-year-old feet wobbled in my heels? All you wanted to do was pretend you were me.” I gently nudge her toward the closet. “They’re for you now, baby.”

She squints more deeply. “Those??”

“Yes,” I say tearfully. “All yours.”

She leans down, peers at the closet floor, wrinkles her oh-so-cool, teen-fashionista nose.

“Eww,” she says.

I snap out of my moment, certain that I misheard. “Excuse me?”

Her nose is still wrinkled, head shaking side to side.

“Eww.”

I silently lead my daughter out of my room.

Close the door. Lock the doorknob. Flip the dead bolt.

Click.

Saturday, 9:59 a.m.

I walk back to my closet and sit back down on the floor.

After a while, I gently lift my beautiful silver Cinderella wedding shoe and hold it up in the light. The tiny pretend jewels on the strap sparkle like diamonds. I place part of one giant Drizella foot into it. I shut my eyes and dream. About all that came before and all that will come after.

I think about my mom.

Then I think about my girl. I smile.

One day her feet will outgrow all her shoes, but she will not have heard it from me.

7.

I WOULD WASH MY HANDS OF THIS IF ONLY I COULD

In the prime of my life, at the pinnacle of my personal power, I have been rejected by another automatic hand-washing system in the ladies’ room.

I wave my hand under the faucet to activate the water. Nothing.

I move to the next sink and wave. Nothing.

I move back to the sink that worked perfectly for the woman who used it right after it didn’t work for me. Nothing.

I try the automatic soap dispenser. Nothing.

I glare at the towel dispenser but do not wave. I won’t give it the satisfaction.

Powerful though I am, I apparently don’t emit enough of an energy field to make the ladies’ room sensors think there’s a human in front of them. In this girl sanctuary, where women come to do many things, including reapply our self-esteem, I’m not even registering as a life-form.

I step away from the row of sinks.

I watch a four-year-old on tiptoes wave her tiny hand under the faucet and get water. Watch a mom wave a baby’s even tinier fingers under the soap squirter and get soap. Watch an elderly woman wave two frail, almost transparent hands at the water, soap, and paper towel sensors and get everything she hoped for.

I step back up and try with a more can-do attitude. Nothing.

The public ladies’ room has always been a humbling place. Waiting in the endless lines . . . praying that the toilets will flush . . . witnessing all the prettier women primping . . . she’s thinner, she’s curvier, better hair, better clothes, better shoes, better everything . . . facing the mirror ourselves . . . doing makeovers . . . rehearsing speeches . . . recovering from tears . . . checking, rechecking, checking, rechecking . . .

We go through enough in the ladies’ room. No one should ever be rejected by the sink. We go through too much outside of the ladies’ room, too. Way too many other situations in which things work completely differently for everyone else than they work for us. Way too many things over which we have no control—even tiny, insignificant things like this.

I glare at the faucets in front of me. Ashamed that I spent even one second letting them get to me. Ashamed that I spent one second feeling ashamed for letting them get to me. That’s how it adds up. Sometimes at the end of the day, when I feel diminished and discouraged and don’t know why, I think that what happened was the equivalent of a lot of little faucets in the world not working when I tried.

I reach into my purse, pull out a small plastic bottle, and squirt antibacterial hand sanitizer in my palms. Rub it in, give o

ne last defiant look to the sensors that didn’t sense me, and head for the door.

I’m almost out the door when I stop myself and turn around. I march back in and place my anti-bac bottle on the counter. Leave it there for the next victim of the sink. This is the ladies’ room, after all. No lady should ever feel alone in here.

TOP FIVE REASONS I DIDN’T EXERCISE TODAY

I don’t want to admit how easy it would have been to start ten years ago.

I feel too fat.

It’s too confusing to pick my activity.

I can’t find a hair tie.

I exercised yesterday and I don’t look any different.

8.

CAREGIVER STANDOFF AT THE ICE CREAM PARLOR

Some families spend summer weekends at their cottage on a lake.

Some go on annual retreats to a mountain lodge.

Some picnic under a favorite tree in the neighborhood park.

Beloved places and traditions that anchor a family in memories and one another . . .

Our family comes here.

Dad welcomes my two sisters and me with a sweeping gesture and a proud voice, as he does each time we visit this place—as if he’s pointing out the captain and first mate deck chairs on a family sailboat.

“I’ll be there, and Mom will be right there!” he announces.

But Dad isn’t gesturing toward deck chairs. There’s no boat. We’re standing at the ultimate eternal vacation destination: the Family Plot.

“Um . . . nice, Dad!” one sister says, looking down at the big blank double patch of grass between other people’s headstones with all the appreciation she’s learned to muster from our previous hundred visits to the plot.

“Such a pretty place,” the other sister echoes on cue, but looking up at the trees, not down at the grass under which Dad is so enthusiastically reminding us he and Mom will be planted.

They’ve been bringing us here for years, so we’re more than a little numb to the emotion of it. We know it’s a great comfort to them to have their affairs in order. Even more, we know it’s a comfort to them to know it will be a comfort for us to have everything in order. We understand that’s why they’ve not only made us visit this place, but the Whole Situation, over and over. They’ve thought of everything, arranged everything; planned for the end of life the same way people plan a wedding.

“Can we go home now?” the third sister—that would be me—mumbles.

“No need!” our joyful mom answers. “I brought the Folder in the car so we can stop for ice cream and review the details!”

Most people do some kind of end-of-life planning, but this is abnormal, I think, as our family gets situated at the large round umbrella table outside an ice cream shop in Sarasota, Florida, where we come after every plot visit. Dad with the double scoop of butter pecan ice cream he always orders, Mom with the modest scoop of raspberry sherbet she always has, my sisters and me with great big bowls of all the flavors of “we do not want to talk about this again.” In the middle of the table, next to the tidy stack of extra napkins Mom always remembers to pick up, is the Folder—containing their neatly organized last wishes, cell phone number of the priest, funeral instructions, headstone inscriptions, drafts of their obituaries, the location of important records, donation preferences, and much more.

Dad’s specific requests, like Dad, are exuberant, detailing lists of invitees and people to notify; noting that Milky Way candy bars and chocolate milkshakes should be served at the reception following his funeral. Mom’s requests, like Mom, are reserved: one Bible verse, one short poem, and one “FOR HEAVEN’S SAKE DO NOT WASTE YOUR PERFECTLY GOOD MONEY ON A PARTY FOR ME WHEN I’M GONE! ABSOLUTELY NO PHOTO BOARD FULL OF PICTURES!” written in such large type it fills up a whole page.

Mom and Dad met at Kent State in their freshman year. Mom was a quiet first-generation college student from an Eastern European immigrant community in Cleveland. An earnest journalism major, with a love of books, ballet, opera, and art. Deeply devoted to her family and community, Mom took a bus home most weekends to help her parents in the small neighborhood restaurant/bar they owned. Dad was a song and dance man, creator and star of Kent State theater productions, part of a well-known local two-man comedy team—Guisewite & Mouse—and president of his class. He swept Mom off her demure little feet, just like in the movies. And here they are a lifetime later, just like in the movies. Mom’s graciousness and Dad’s gregariousness blended somehow into a team that has ushered my sisters and me through life with a way of looking at almost everything with hope and humor.

This explains why the dreaded grief-filled Folder that’s lying in the middle of the ice cream parlor table in front of us is labeled “The Grand Finale!” in cheery bright red pen. As though it contains the program for a thrilling event, not the details for one of the most dreaded ones. Details our parents have meticulously planned so my sisters and I will never have the wrenching experience of not knowing what to do because no one could stand to discuss it.

After a few bites of sherbet, Mom puts down her spoon, picks up the folder, and begins the familiar review for my sisters and me.

“Do NOT let them talk you into an upgraded casket!” she proclaims. We’ve heard this speech so many times, we could recite it in unison. “We’ve prepaid for cheap ones! Nice, basic, cheap! Don’t let them prey upon your emotions and talk you into something with a bunch of frills we don’t want!”

“We will not care how the casket looks after we’ve croaked!” Dad adds. “Also, don’t let some overeager funeral director convince you to spring for an expensive celebration-of-life venue! No kickbacks to fancy caterers and florists! The church social hall is just fine!”

“But not for me!” Mom reminds us, flipping to her No Party page. “Remember: Under no circumstances is there to be a big party for me!”

“Of course they’ll have a party for you! Your girls love you!” Dad counters, as he always does.

“My instructions clearly state NO PARTY!” Mom replies, as she always does, waving the page in the air. “I will NOT stand for a party!”

“Well, you won’t be standing, but if I’m still here, there’s going to be a party for you! A beautiful party with pictures and a video!” he insists with a charming song-and-dance-man grin, reaching over to give his bride a loving squeeze.

“NO!” Mom protests, waving her page more vigorously in the air. “NO PICTURES! NO VIDEOS! NO MAUDLIN SONGS! Absolutely no sneaking around behind my dead body!”

This devolves into the regular discussion of which one of them is likely to “croak” first . . .

Which devolves into a new round of promises that the sisters will listen to the wishes of the deceased parent, not the wishes of the non-deceased one . . .

Which wraps up, finally, in a long, long, long review of where every single piece of paper pertaining to anything important is located. Followed by a rereading of their wills and powers of attorney. Followed by the whispered verification that we’ve all memorized the location of every hidden key as well as the secret combination to their safe, which contains duplicate copies of everything we’ve just discussed for the hundredth time . . .

My sisters and I come to Florida often to visit Mom and Dad. We usually come separately so we can have our own time with them, but also so our trips will be spaced out and there won’t be long periods with no one seeing how they’re doing. They’re both amazingly healthy, but every birthday makes us more nervous to live so far away. We had a sister conference recently and decided to make this visit together so we could bring our own uncomfortable topic to the ice cream table. We rehearsed how to present it with the flair and good nature we learned from our parents. Surely these optimistic, pragmatic people, who have so carefully planned for everything, who are so open to discussing all the icky topics, will appreciate what we want to do just as we appreciate all t

hey do to protect us.

Mom is tucking the last pages of their end-of-life review back into the Grand Finale! folder. I exchange a nod with my sisters, open my oversize purse, and pull out a folder the three of us have prepared.

“You’re doing so beautifully, Mom and Dad,” one sister begins.

“You’ve thought of everything for us, and now we’ve thought of something for you!” the other sister continues.

“And now,” I say, proudly, holding up our folder labeled in an equally cheery bright red pen, “we present ‘The Next Adventure!’”

Mom and Dad go blank. Before I can stop him, Dad plucks the folder from my hand and pulls out one of the several pamphlets inside.

“Assisted-living facility?” he asks, staring at the pamphlet, looking as stunned as he sounds.

“No, no, Dad!” I answer, trying to speak with even more lilt in my voice. “Let’s think of it as the Next Adventure!”

“Graduated care community??” Mom asks, sounding equally stunned as she picks a different pamphlet out of the folder.

“It’s nothing you need today, but things could start to change, and we think it’s time to plan for the Next Adventure!” I whip my head toward my sisters, silently imploring them for backup. “Don’t we??” My sisters are useless. Caught off guard and struck mute by our parents’ bad reaction. Either that or they’re simply relieved that I, not they, have the floor and are happy to let me flounder on my own.

I try to summon the inner resolve I had when I was preparing my daughter for the beautiful life changes that awaited her, but I’m no match for the parental unit. Mom’s ninety years of experience have somehow enabled her to achieve a geriatric glare and a preteen stink-eye at the same time, so it’s as though both my mother and my daughter are staring at me through the same face.

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault